Josh, why are you doing this?

Friends and detractors alike have asked me this same question over the last few weeks. Why enter the decades-old debate regarding KJV-Onlyism? Why go public with my views rather than keeping them to myself and my church?

It’s because I want to stay in unity and fellowship with my brothers who use the KJV, but some of them have made exclusive use of the King James Version into a test of fellowship—and even of doctrinal orthodoxy. They need to know that I have good and even biblical reasons for why I have moved away from using the KJV in public ministry. Mainly: I believe the Bible should be accessible to the plow boy.

I will give three reasons for my viewpoint.1

1. The Bible says we should use words people can understand.

The first and most important question we should ask is the same one I was taught growing up in a Baptist church: what does the Bible say? In the midst of all the discussion on Bible translation, we often forget to reference the Bible. So then, what does the Bible say about Bible translation? Well, surprisingly little. HA! Don’t you wish there were a verse in the Bible that said it clearly? “Thou shalt never translate the Bible out of its original language.” “Thou shalt forevermore use the King James Version.” Or even better, “Yo bro! God’s Words are legit! Just get ’em out there. It’ll be lit.” And though the Bible says little about its own translation, it does say a few things that are important to remember when approaching God’s Word.

The Bible says we should use words people can understand if we want to edify them. I have come to realize that people we serve—and I myself—do not really understand the KJV. Not fully. Not as fully as I would have if I had lived in Elizabethan times and spoke their English.

This doesn’t mean that I don’t understand any of the King James Version. It just means that throughout my thirty-year Christian journey I have found myself often needing to reference newer translations of the Bible in order to understand God’s inspired words.

The Bible hints at the importance of using people’s common speech in several places, such as Nehemiah 8:8 and Acts 2. At Pentecost, Parthians, Medes, Egyptians, and a host of other nationalities heard God’s word in their own languages (Acts 2:8–10). This miracle was a testimony to the truth of the disciples’ Spirit-inspired message—and to God’s intent to bless all the families of the earth. God’s power is not limited to one geographic location, to one time period, or to one human language. If God can speak Elamite, he can speak contemporary English.

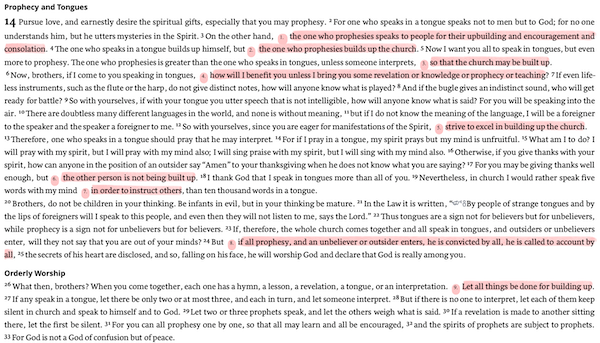

Paul supports this principle, too, when he argues with Corinthian believers who are abusing the gift of tongues that the Spirit gave at Pentecost. They were using words others couldn’t understand. Paul says repeatedly in 1 Corinthians 14, in various ways, that if you want to edify people you have to use words people know.

Unless you utter by the tongue words easy to understand, how will it be known what is spoken? For you will be speaking into the air. (1 Cor. 14:9 NKJV)

The KJV is not as unintelligible as a completely foreign language, an “unknown tongue.” But Paul’s principle still applies: if we use words people can’t understand, they will not be edified.

Language changes over time. Elizabethan English has slowly become, at places, difficult or even impossible for the modern plow boy to understand.

Noah Webster, author of the dictionary trusted and used by many KJV readers, saw this very thing in his day. He said a few years after his dictionary released in 1828,

Some words [in the KJV] have fallen into disuse; and the signification of others, in current popular use, is not the same now as it was when they were introduced into the version. The effect of these changes is, that some words are not understood by common readers, who have no access to commentaries, and who will always compose a great proportion of readers; while other words, being now used in a sense different from that which they had when the translation was made, present a wrong signification or false ideas. Whenever words are understood in a sense different from that which they had been introduced, and different from that of the original languages, they do not present to the reader the Word of God.

What Webster said is even truer today, and if we didn’t all feel social pressure to deny it, we would see it, too. Every generation must continue the cause Luther, Wycliffe, and Tyndale fought for. We must get the Word of God into the language of the common man. That task didn’t end in 1395 (when Wycliffe’s Bible was completed), or in 1611 (or 1769!). We must get the Word of God into the living hands of what the KJV translators called—in their oft-forgotten preface—the “very vulgar.” We must give God’s words to the plow boy for whom Tyndale gave his life.

2. The KJV contains not just “dead words” but also “false friends.”

Webster’s point above is why the most important chapter in Mark Ward’s book, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, is entitled “Dead Words and False Friends.” This chapter answers the most common objection raised by those disinclined to acknowledge new English translations of the Bible: Why don’t you just give your folks a good dictionary and let them look up the words they don’t understand?

For one thing, isn’t it a little strange that we insist people look up the word besom when they already know “broom” (Isa 14:23)? And why should plow boys have to look up chambering when they already know “immorality” (Rom 13:13)? Why make English speakers look up emerod when they already know the word “tumor” (1 Sam 5:6ff)?

These words are what Mark calls “dead words.” Dead words aren’t the KJV translators’ fault. Those words did exist in their English. They just don’t exist in ours. We use different words for those same things.

But, my friends, the biggest problem with insisting on the exclusive use of the KJV today is not the dead words. It’s not, as Mark says, the words we know we don’t know. It’s the “false friends,” the words we don’t know we don’t know.

Mark gives a bunch of examples of words (and other things in English beside words) that we all grew up reading and repeating and memorizing that didn’t mean in 1611 what they mean today. They tripped up Webster’s contemporaries 200 years ago; they trip us up, too, without our even knowing it.

Ironically, even the famous verse used by so many of my KJV-Only pals to call for faithfulness to the KJV—“Remove not the ancient landmark”—didn’t mean in 1611 what those words mean today.

Same with, “How long halt ye between two opinions?”

Same with, “But God commendeth his love toward us.…”

(To find out what these mean, you have to read the book.)

It’s one thing to ask people to look up words they don’t know when words they do know are available. That’s not ideal, but at least common people will know when they don’t understand these “dead words.”

It’s another thing to insist that people read a Bible translation that uses words from a different English that they will necessarily misunderstand. These words are “false friends.”

3. The time for change is now.

I’m not criticizing the KJV in the least. The KJV translators did an excellent job translating the Bible into their English. However, they did translate it into their English.

I’m not saying that you don’t understand the KJV at all or that your congregants are incapable of understanding this historic translation at all. And I’m not saying that all use of the KJV is wrong (I still use it in personal study). Furthermore, I’m not saying that those who preach from the KJV are sinning. And I know that modern English and Elizabethan English overlap significantly. So good men can disagree over when the differences between the two become too great and a new translation must take the place of the KJV.

Personally, I think the time is now. What made me come to this conclusion?

Expository preaching was the catalyst that made my heart cry out for a Bible in the language of my mission field. I’ll never forget preaching through the book of Ecclesiastes a few years ago. I was a dedicated KJV preacher who had never delivered a sermon from any other translation. Though I had often referenced other translations in my personal study and had done my personal devotions from modern translations, I had never crossed the line into preaching from another version of the Bible. As I made my way preaching through books in the King James Version, I continually found myself getting tripped up. It wasn’t so much in my time of study, but in the moment of delivery I had the greatest trouble.

I found myself spending several minutes per sermon (a few times up to ten minutes in a forty-five minute sermon) explaining, not the meaning of the text but the meaning of the archaic language and (to our ears) awkward syntax of the KJV. This unnecessary hurdle not only inhibited my delivery but caused confusion in the pews. After I was finished explaining the Elizabethan English I would then begin explaining the meaning of the actual passage. And what I ended up saying the verse meant was often precisely what a modern translation already said. This all left less time for illustration and application. In short, this unnecessary hurdle was consuming too much of my limited preaching time. Since the Bible does not teach me to expect any translation to be perfect (and the KJV translators specifically say that their work was not perfect), I felt free to search for a modern translation that I could trust from a textual source I saw was historically trustworthy.

One-on-one discipleship also convinced me to look for a translation that I could hand to a blue-collar, Las Vegas, newly-minted disciple of Jesus. I often felt badly giving a new believer a copy of Scripture, telling them to read it everyday, knowing that they would comprehend only portions of what they read. The amount of “dead words,” “false-friends,” and archaic syntax found in the KJV worried me. I felt as if I had not given them the very best start in this new Christian faith. Too often I would hear things like, “I never understand anything I read in the Bible, but when I come and hear you teach I finally get it.” I would love to think (and probably did) that this had something to do with my oratory ability, when in fact it had more to do with a modern Christian needing a teacher not only trained in theology, but also conversant in Elizabethan English. I wanted so desperately for my new converts to have a Bible in their own English.

So, I think the time is now, and I ask my brothers who disagree: if not now, when?2

Answers to counterarguments

This case I’m building isn’t new. And as soon as I make it, I know the counterarguments I will hear. I have heard them my entire life.

I will borrow here again from Mark’s book, specifically chapter six.

1. Why dumb down the Bible?

But putting the Bible into our English is not the same as dumbing it down. In some places God inspired the Bible’s content to be difficult; those places should remain difficult. But the English should be accessible to the common man.

2. The KJV sounds like God’s Word. Modern versions are pedestrian.

This begs the question: what does God’s word sound like? God chose the common languages of ancient plow boys; we should use language accessible to plow boys today.

3. The KJV translators chose timeless language. Trust their wisdom.

There is no such thing as timeless language. Language always, always changes. The KJV translators were not KJV-Only; they would have supported the ongoing work of revision—because their own Bible was a revision of a previous translation!

4. Thee, thou, thy, and ye are more accurate than modern English pronouns.

I acknowledge the truth in this argument but believe that all translation involves compromise. No known English, for example, has plural and singular versions of whom like Greek does, and no one complains.

5. English has not evolved but devolved into a base and ugly language.

Come on! Look at the works of C.S. Lewis—a twentieth-century English prose master.

6. What about the italicized words?

Italics are helpful to people who know Hebrew and Greek, but they don’t actually help English readers understand the Bible.

7. The KJV is easier to memorize.

Because you started memorizing it when you were a kid, the time of life when memorization is easy!

8. The KJV is a literal translation. Other versions are simply paraphrases.

The NKJV and MEV are literal translations into contemporary English, and they use the very same textual basis as the KJV.

9. Modern versions are based upon corrupted texts.

Fine. Then make or use a translation of whatever texts you prefer into contemporary English accessible to the plow boy. Such as the NKJV and MEV.

10. The problem really isn’t that bad.

Thankfully, the KJV is not (yet) a Vulgate. Simple people can read it and get tons of truth out of it. But they would get more if the Bible were in their English.

Going back to my first post in this series of three: if your real issue is the original language texts, then why not read a translation of those same texts into the English we all speak and the plow boy understands?

Going back to my second post: if independent Baptists have not always believed in the perfection of the KJV, then it is possible for us to move back to the position of John R. Rice: appreciation for good contemporary translations.

Take a step

Here are the action steps I suggest.

1. Allow for autonomy; work toward unity.

It will not be easy for some of my friends to make a switch away from the sole use of the KJV in public ministry. For a few of you—this is probably something you should NOT do. I spoke with an independent Baptist pastor who has been preaching for nearly 45 years. He said to me that I was absolutely right in my writings about this issue and the history of this controversy. But he also said that he was too far into his ministry to personally consider a transition. “Like a carpenter who has used the same hammer for 45 years, I know my tool and how to swing it.” To my elder brothers I say, “Bravo! Do what you must as you continue to reach your community with the gospel of Christ.” But consider this. Make a little room at the table for a guy like me.

I’d love to remain an independent Baptist. I say this on behalf of many non-KJV-Only pastors. I’d love to continue supporting independent Baptist missionaries, sending my students to independent Baptist schools, and attending independent Baptist fellowships. Will my KJV-Only brothers allow this? I’d love to see the independent Baptist movement return to the core value of local church autonomy while being true to the biblical principle of Christian unity. Would my KJV-Only brothers allow us to remain independent Baptist without demanding that we use your preferred version of the Bible?

2. Be bold; use the Bible translation you believe is best for your flock.

To those of you who, like me, have no theological qualms with a modern version of the Bible but have yet to transition away from the KJV—I have a few words. Proceed very slowly and with great caution out of love for your sheep. Many of them have been taught for the last 35 years that the KJV is perfectly inspired and the only trustworthy Bible in the entire world. They will see this transition at the same level of heresy as denial of the resurrection or the blood atonement. Some of those we shepherd have heard more sermons on Bible translations than on substitutionary atonement. Remember what Paul told Timothy.

A servant of the Lord must not quarrel but be gentle to all, able to teach, patient, in humility correcting those who are in opposition, if God perhaps will grant them repentance, so that they may know the truth, and that they may come to their senses and escape the snare of the devil, having been taken captive by him to do his will. (2 Timothy 2:24–26)

It may cost you dearly in finances, fellowship, and friendly fire to use the translation you believe is best for your flock. But those who can move forward should not stay where you are: you should take a step in the biblical direction—because the Bible values intelligible language, and the plow boy needs it.

3. Buy this book.

I’m certain you have far more questions than my simple blog series could hope to answer. Therefore, I want you to go and buy my friend Mark Ward’s book, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible (paper, Kindle, audio, Logos). It’s short and (appropriately!) easy to read. Mark also put out a film version of the same material on Faithlife TV, and it’s now available on DVD.

Thanks for reading these VERY LONG articles. I’m sure there are folks who would like to dialogue. I encourage questions and statements from each of you. Feel free to comment below. Matthew Lyon, Mark Ward, and I will attempt to answer each one.

Notes

-

I relied heavily on my friend Mark Ward, author of Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible (and one of my rafting pals from a creationist trip down the Grand Canyon this past summer!), to put these reasons together. ↩

-

Ironically, I think the strongest defenders of the KJV have already made my case. Many of them have put out long lists of archaic words in the KJV, along with definitions for modern readers. D.A. Waite has his Defined King James Bible, which is chock full of footnotes pointing out places where modern readers will stumble over Elizabethan verbiage. As I see it, they have diligently collected a bunch of evidence refuting their position. ↩

Great article. The point of the whole argument is that God’s Word must be accessible to people. This article stands in the long, noble tradition of faithful Christians translating the Bible into the common tongue.

Friend you used verse out of content regarding speaking in tongues. Remember this is in reference to people speaking in DIFFERENT languages not people having a hard time understanding the same English language.

Paul, this is a common objection I get to the same argument from 1 Cor 14 in my book. You are certainly right that in 1 Cor 14 Paul applies the principle to tongues speaking, but surely the principle—edification requires intelligibility—applies to all speech in church. If a preacher gets too academic and starts using words like “pericope,” “protasis,” or “participle” in his preaching (without explaining them), he is using unintelligible speech and failing to edify. If a preacher tosses Greek or Hebrew words into his message without explaining them, he’s doing the same. KJV English is somewhere between fully intelligible and fully unintelligible. Would Paul be happy with a situation where Bible readers are being warned against “chambering and wantonness” when they could read instead, “immorality and promiscuity”? Would he be happy with a situation in which Bible readers are encountering “false friends,” words they don’t even know they don’t know? 1 Cor 14 tells me he would not. Of course, we don’t drop a Bible translation the instant one word starts to be unfamiliar. But if Noah Webster made the same complaint Josh and I are making, and he did so almost 200 years ago, perhaps it’s time to agree that there is too much unfamiliar and even misleading English (because of language change) in the KJV.

I trow that what thou sayest, thou hast well said.

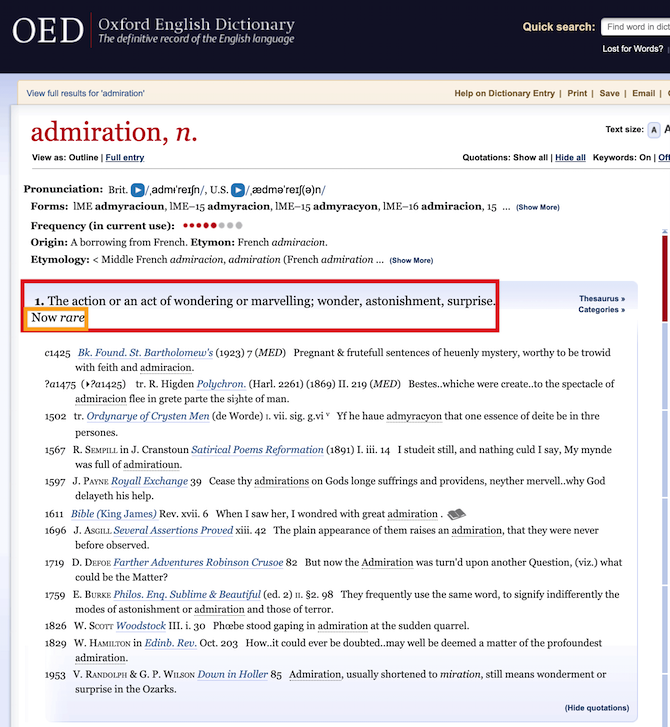

A classic “false friend”:

“And upon her forehead was a name written, MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT, THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH. And I saw the woman drunken with the blood of the saints, and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus: and when I saw her, I wondered with great admiration.

Revelation 17:5-6 KJV

Admiration does not mean what you think it means…

Great article one again.

Nathan W, that’s a great one! Hadn’t spotted that one before. Classic false friend.

“Admiration” to us means “respect and warm approval.” It’s possible that a sharp KJV reader will notice that it feels a little weird for John to show respect and warm approval to the mother of harlots. But most people will see the word “admiration,” will use our current sense of the word to make some sense of the sentence, and will move on.

The Oxford English Dictionary—the only dictionary that records the entire history of English rather than simply a then-current snapshot—shows that there is a “now rare” sense of “admiration” that fits the context perfectly. In other words, *the KJV translators did not make a mistake.* They had a sense of the word that isn’t really available in contemporary English. This happens a lot.

We still use the word “admiration”; we just don’t (and can’t) use it that way anymore. Language changes.

All the modern translations go with “amazement,” “astonishment,” or something like those. That is an accurate reflection of the Greek in our English.

If you bothered to read the next verse, the context of Revelation 17 will tell you.

“And the angel said unto me, Wherefore didst thou marvel?…”

Common sense would tell you that John the Beloved wouldn’t admire a whore.

Also, is this too plowboy:

“Da angel messenja guy tell me, “Eh, how come dat blow yoa mind? I goin tell you da secret bout da wahine dat ride on top da Wild Animal dat get seven head an ten horn.”

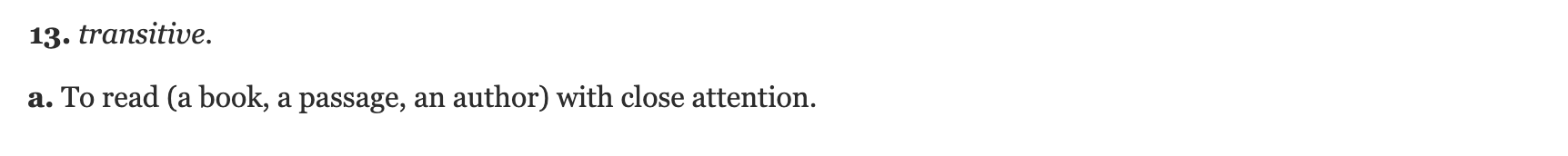

No wonder all the modern versions remove “Study” from II Timothy 2:15.

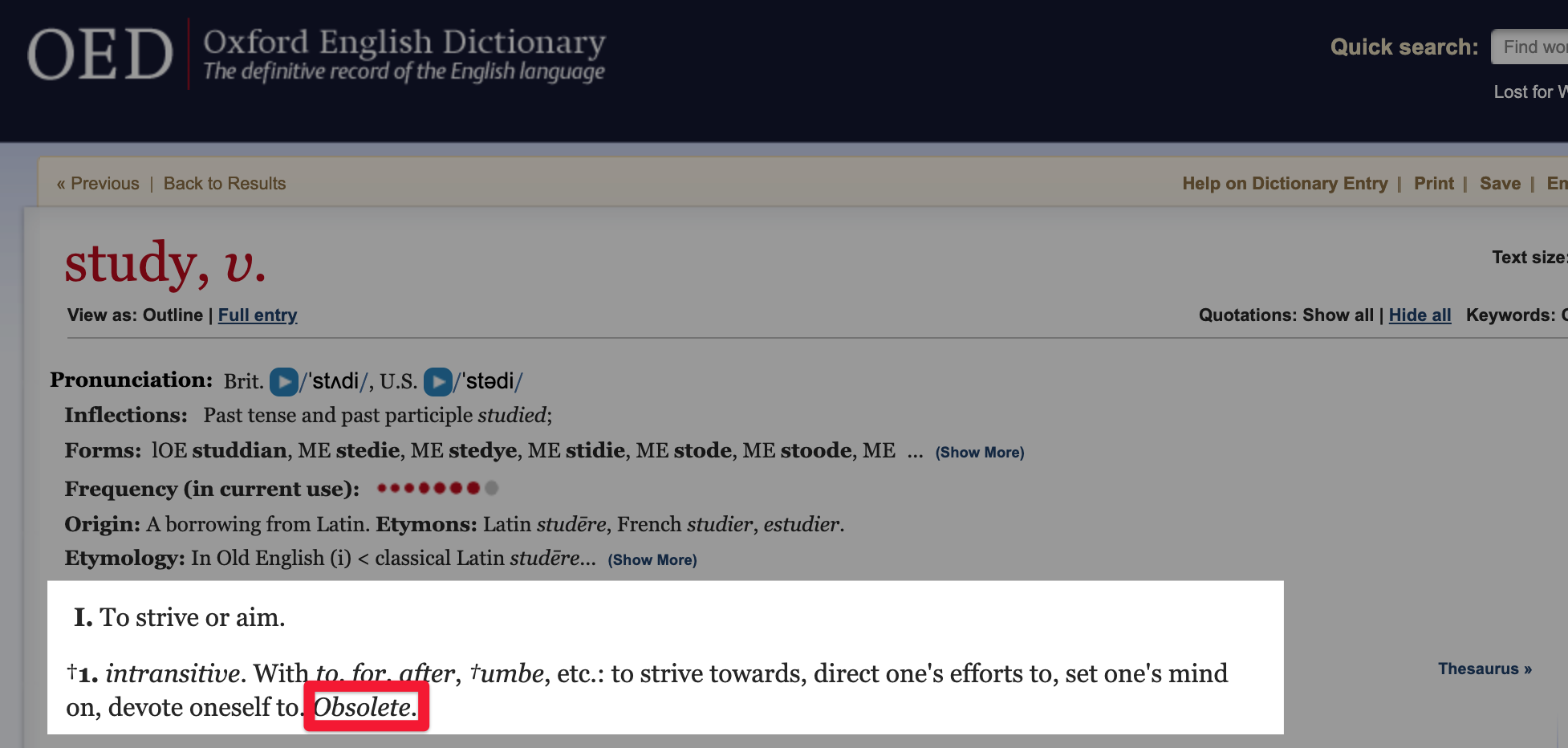

Ed, what did “study” mean in 1611?

Here’s what it means in a context like 2 Tim 2:15 today:

Here’s what the Oxford English Dictionary says it meant in 1611:

This is another classic “false friend.” “Study” in 2 Tim 2:15 in the KJV in 1611 meant “strive to…”—which is actually what the Greek word means. “Study” did not mean “read with close attention,” as it does today because of language change. The KJV translators didn’t make a mistake, and modern readers are not dummies for misunderstanding what they wrote. Language simply changes over time. It is ironic, however, that you would cite this verse.

Friend, you also quote the Hawaiian Pidgin New Testament. Do you have any knowledge of how Hawaiian Pidgin functions on the Hawaiian islands? Wikipedia says it is “a full-fledged, nativized, and demographically stable creole language.” Would you tell people who speak that language on a daily basis that they may not have the Bible in their own tongue? Who gets to have the Bible in their own language, and who has to learn the socially dominant language of their area in order to read the Bible?

Good question about the meaning of “study” in 1611, Mark. Unfortunately, you are not presenting an accurate picture of what Oxford English Dictionary actually says. The website you reference wouldn’t have the complete OED on it (probably because of $$), if that is legitimately all you find there, but you have no excuse, having access to the full OED somewhere in your vicinity at some library, or maybe even at BJU. Therefore, please don’t forget that the full presentation about the word “study” as a verb has as its preliminary definition (Intransitive uses, 1.a.): “To apply the mind to the acquisition of learning, whether by means of books, observation, or experiment”, and the examples go as far back as 1300 up through and past 1611. Therefore, in 1611, they absolutely understood “study” in 2 Tim. 2:15 how we would understand it today, and, therefore had that in mind as to be the preliminary idea to the term as they used it in 2 Tim. 2:15. And they put that as definition #1 in the full OED, not some abbreviated online version. I have the full OED on my computer (which costs more than $200), and saw quickly you weren’t reading the full thing. Others that have the program or can also go to a library with it can see quickly your conclusions are wrong. The definition you are trying to say they only knew it as is #4.a. in the full OED (the second to last of the intransitive uses).

Also, at the funeral of Lancelot Andrewes in 1626, one of the KJB translators, a man said of him something that would make no sense in how you want to allege they only understood it in 1611, “His late studying by candle, and early rising at four in the morning, procured him envy among his equals…” (Lancelot Andrewes, Ninety Six Sermons, Oxford, vol. 5, 1841, p. 289). There are other examples within the sermon in question. Lancelot Andrewes himself used it in this way, “For when we read, what do we but gather grapes here and there; and when we study what we have gathered, then are we even in torculari, and press them we do, and press out of them that which daily you taste of.” (Lancelot Andrewes, Ninety Six Sermons, Oxford, vol. 3, 1841, p. 77). Also, Hadrian Saravia, another KJB translator, said, speaking of the possibility of having laymen as Bible teachers in a church, “There is no doubt but that the custom in question was derived from the Apostles; for although men are rendered powerful in the Scriptures only by the gift of the Holy Ghost, this gift is not such as to supersede laborious study and diligence on the part of those who would become versed in them.” (Hadrian Saravia, A Treatise on the Different Degrees of the Christian Priesthood, Oxford, 1840, pp. 271-272). Sounds like the kind of study as we know it today, and in context with the Bible, as is 2 Tim. 2:15. John Rainolds, another KJB translator, said, “Whether Moses were read in David’s time, we cannot certainly affirm; yet certain it is that David, whose whole delight and study was in the law of God, as may appear.” (John Rainolds, The Prophecy of Haggai, Edinburgh, 1864, p. 50). That all sounds the like the learning kind of study, and I would assume most everyone could see these and come to the same opinion. Hence, your information and conclusion are wrong. Please retract it so it doesn’t mislead others.

Daniel, I’d like to use one OED word, if I may: “sheesh.”

Brother, I have access to the full OED, and it was rather presumptuous of you to charge me with inadequate study (ahem). The screenshot above is from the full OED, provided to me by my local library system. I use the full OED probably ten times a week. (And note that I quoted sense 13—a screenshot from the full OED.)

Now, I never denied that “study” could be used in 1611 the way we use it today. You are 100% correct that the KJV translators had the same sense available to them that we have today, namely, “To apply one’s mind purposefully to the acquisition of knowledge or understanding of a subject” (AHD).

What I deny is that the KJV translators used that sense in 2 Tim 2:15. Instead, they used a different sense of the word that is no longer available to us.

How do I know this?

Because the KJV translators could read Koine Greek, and so can I. And the word they are translating here (which is precisely the same in all TR editions and all critical texts) is σπουδάζω (spoudazo): “to be especially conscientious in discharging an obligation, be zealous/eager, take pains, make every effort, be conscientious” (BDAG). Modern translations go with “Do your best to…” or “Be diligent to…”

I look at the list of senses of the word “study” that were available to the KJV translators in 1611, and I see one that fits σπουδάζω (spoudazo) perfectly, the one I took a screenshot of above.

Then I look at the other time “study” is used in the KJV. I think they *did* use the “acquisition of knowledge” sense in Ecc 12:12, and the context tells me so—that’s the verse that sighs about the making of many books. But I don’t think they used that sense in 1 Thess 4:11—“Study to be quiet.” What, are we supposed to apply our minds purposefully to the acquisition of the knowledge of quietness? No, we’re supposed to aspire—to do our best, to be diligent—to live quietly. (Again the Greek supports this interpretation.)

“Study” in 2 Tim 2:15 in the 1611 KJV did not mean what nearly every KJV reader I run into thinks it means today. It meant to be diligent, not to hit the books.

Though I will of course be the last person to discourage anyone from hitting the books, even and especially the full OED.

Hey, Mark, I’m not trying to be testy to you, but I was giving a reply to your comment that the word meant only your preferred meaning in 1611 which you think is the only thing it should mean there in 2 Tim. 2:15. Ok, it was presumption to say you didn’t have access to the OED. Sorry to offend you. I don’t know though what you have access to, since I use the CD program which is of the second edition (1989), so the numbers of what you cite don’t seem to match. Nevertheless, some version of the full OED properly refutes your original assertion, which you somehow are now abandoning, claiming something different instead.

As for this particular comment, so you deny that the word as used in the KJB means study as we would assume today, as applying one’s mind to material to learn something. Again, I’m not trying to be testy, but, maybe it is not the majority of KJB readers that are getting it confused but you rather… You have to ask yourself whether God would allow a mass delusion of His believers who are trying to be led by the Holy Spirit, to by and large conclude similarly on the meaning of the word there, yet in opposition to your preferred, subjective meaning.

For example, Matthew Henry, one of the most read Bible commenters, who also knew Greek, being able to read it by age nine, has in his commentary about 2 Tim. 2:15 the following, “Ministers are workmen; they have work to do, and they must take pains in it… And what is their work? It is to rightly divide the word of truth… It requires great wisdom, study, and care, to divide this word of truth rightly; Timothy must study in order to do this well.” Sounds like he understood it the learning kind of way and would side with modern KJB believers.

So, you self-admittedly have a minority opinion about the meaning there in comparison to those who actually use the KJB. You contend instead to follow whatever some scholar says about it, someone whom I don’t know, nor probably would assess I could support the background of or methods of research, such as your BDAG you quote. It thus appears that you contend there is no sufficiency of the scriptures and the sufficiency of the leadership of the Holy Spirit unless people pair them with BDAG. That’s a new doctrine. Do they in your BDAG recognize that spoudazo is the basis to the main word in modern Greek for student, which is spoudastis? Spoudazo is also one of the main words in modern Greek for study as the learning kind. Are modern Greeks mistaken therefore?

Therefore, in essence, in English you are saying the majority of readers of the KJB are mistaken, and also in Greek the majority of modern Greek speakers are wrong when they use a word for study and student. Nonetheless, I’m just not buying it.

Daniel, I’ll let my case rest. I do believe that the vast majority of KJV readers—including myself for many years of my life—have misunderstood the word “study” in 2 Tim 2:15. I don’t blame them. I don’t blame the Spirit. I don’t blame the KJV translators. I “blame” the inevitable process of language change.

?? Aw, come on, Mark, you can’t let your case rest when you don’t have compelling enough evidence. Whatever you’ve said thus far is simply not compelling enough. BDAG is rife with corruption from CT scholarship and is therefore unreliable. All Koine Greek scholarship after the end of the 1700’s on up to now is questionable at best since they started mixing definitions with secular usages. That is unacceptable because Christians will use terms, like “love”, that unbelievers will all the time misunderstand with their own connotations. At worst, scholarship like that is corrupted with outright unbelief. That is why I pointed to Matthew Henry, who predated that.

Nevertheless, let’s look at how someone more contemporary had put it–Noah Webster. Since you don’t hold to any authority of the KJB, I appeal to what he did, and, if you will look at his translation of 2 Tim. 2:15, he put “Study”. The man was brilliant, starting to study Greek at age 14, and eventually learning 28 languages just to do his dictionary. I don’t look to him as the authority, but he surely knew Greek better than you to have nevertheless put “Study” there, his primary meaning he gave to it being “To fix the mind closely upon a subject; to muse; to dwell upon in thought” and then secondarily “To apply the mind to books”. His tertiary definition was “To endeavor diligently” and he did refer to 1 Thes. 4 with that definition, but not to 2 Tim. 2:15. I’d assess it as that he meant #1 or #2 therefore for what he put in 2 Tim. 2:15.

You neglect to mention that spoudazo is in other places, and that in many of those the KJB translators did as you insist subjectively is the meaning in 2 Tim. 2:15. Two chapters away, twice they translated spoudazo as “Do thy diligence” (4:9,21), and then in Titus 3:12 and 2 Pet. 3:14 they put “be diligent” and in 2 Pet. 1:10 they put “give diligence”. So, sure, spoudazo can mean what you allege. However, in 2 Tim. 2:15, if it ONLY meant that, the KJB translators would have only put that, as the NKJV and modern versions do. Since they did not, and since they put “Study”, they proclaim that it ought be primarily understood in the learning kind of meaning, by the very fact that they did not put “give diligence” or something similar as in about every other place, and by the fact that there is an inferred subject in context as to the object of study, the “word of truth”. There is a reason why they put “Study” instead, and it is not the reason you are thinking. It is not to say only “give diligence” or they would have been plain enough about it. They wanted people to also, or primarily, infer the learning kind. They didn’t make a mistake. It is only modern folks like yourself making a mistake, alleging it should be “Give diligence” there or something similar. I think they knew Greek a whole lot better than you do. No disrespect intended.

Thanks Josh; Gracious, insightful, honest, and likely very helpful to many. Good friends of mine still use their KJV, an I do fine with it. But I wonder how one unfamiliar with the “dated” language can receive the full benefit of God’s Word. I made the move to ESV several decades ago, however I still appreciate the KJV. But, when I preach and teach, I want everyone one listening to understand what God’s Word is saying.

Very much have benefited from both these articles as well as Mark Ward’s book. As a student at an IFB school I’ve been asked many questions as to why I, a ministerial student who should obviously know better, use the ESV. I’m very thankful for you both helping me in my endeavors to “give a reason” as 1 Peter mentions. It was very refreshing to hear someone address the issue without attacking anyone (a problem I’ve faced on both sides of this issue)

Did it ever occur to the opponents of the KJV that it was the only Bible used (and accepted) by the church from 1611 until 1881-85 when the English Revised Version (ERV) was published? That version was limited acceptance in the U.S. and in Great Britain mainly used by the preachers and scholars. It became the authorized revised version of the Bible. It lost its glamor and was not widely used and is published only by Cambridge University Press in a KJV/RV interlinear edition. It never gained acceptance by the people like the KJV. The publication of the American Standard Version (ASV) was the version prepared for the U.S. (based on the ERV) and found limited acceptance. The KJV dominated the church scene for over 300 years and is still the version by most people who trust the scripture to be accurate. It is the only version of the Bible based on the Textus Receptus (TR). Even the NKJV is excluded from the TR tradition and is supposedly based on the “Majority Text.” It can be proven to be sympathetic to the Critical Text tradition and many places can show where the NKJV is not translated from the Majority Text.

The Levitical Priests of the OT were custodians of the Bible text. They were called “scribes.” They had the responsibility of seeing that the text of the scripture was kept pure (Psalm 12:6; 119:140; Prov. 30:5). The local church (through the priesthood of the believer) has taken the responsibility of the custodial care of the scripture. That same church accepted the TR and it held dominance in the world of the church from 1516 until 1830 (when Karl Lachmann wanted to dethrone the TR). It would seem that the Bible that produced the Reformation in the 16th century, revivals in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the great missionary movement in the late 19th century and the early 20th century would testify to the authority of the KJV and its God-approved use. Only until some “scholars” (mostly German-trained “higher-critics of the Schleiermacher tradition) decided that the TR was no longer accepted and they wanted another Greek text that they deemed “better,” did the KJV become a “step-child” to the liberal church. Today even some who claim to be Fundamentalists have decided the KJV is out of date and “archaic.” To this writer that is developed from a mindset of unwillingness to learn the vocabulary of the KJV and it’s accuracy (“ye, you, thee, thou, -eth,” et al) when the translators sought to duplicate the Greek “persons” and “verb” tenses with the above examples. The new translations have been successful in “dumbing down” the scriptures. Remember, the KJV has a 5th to 6th grade reading level while most new translations are in the upper levels of education such as 10th-grade and 11th-grade reading levels. Taking into account the current tragedy of the education system in the U.S. most people graduating from high school do not have a reading level of a middle school student. Why promote something that will not help the people know the word of God?

Postscript: Someone will object to the above assessment and say, “Well the Pilgrims brought the Geneva Bible to America.” Question. Why did the Congress of the United States approve the printing of the KJV for use in the public? I have two KJV Bibles published by the U. S. Government. One is a Bible for use in public schools and the other for use by the U. S. Military. I even have an Elementary Primer to be used in the public schools that is a “responsive reading” book authorized for printing by the Library of Congress in 1805. All of the scripture used is KJV. The Pilgrims were the only people using the Geneva Bible.

Jerry, many of your specific claims are answered in my book. For example, I have an entire chapter in my short book about Flesch-Kincaid reading level analyses of the KJV. I welcome your feedback on the book.

And I must say straightforwardly: what you say about the NKJV is simply and clearly false. The NKJV and MEV (and several other translations) are based on the same original language texts the KJV is. The KJV is not the only English Bible based on the Masoretic Text and Textus Receptus.

Mr. Ward, I appreciate that you read what I wrote and thank you for your response. I have looked at your book’s contents and decided that I have heard most of the things you bring against the KJV. You may not know where I came from. There was a time when I preached from the NASB and NKJV. I studied textual criticism under Dr. Harold Hoehner. Was taught preaching under Dr. Haddon Robinson. There was a time when I used the same arguments you use in your book against the KJV. Then a friend pointed out to me the dishonesty of the editors of the USB text from which I learned to read the Greek NT and found out that most of them, if not all were probably not believers. I came to the place where I was directed to the books by Edward Hills and that convinced me that maybe I should reconsider my position, which I did. I grew up on the KJV but the critics at Bible College and Seminary led me to believe that the “new” translations were better, especially the NASB which was a literal translation of the Greek and Hebrew. The only problem is the NASB was from different Greek and Hebrew texts. So I doubt you can tell me anything I don’t already know about the arguments against the KJV. As far as the NKJV is from the wrong text is provable. It is in the line of the NASB with its “NU Text reads” in pointing out that the Bible probably does not say what the Bible says and cannot be trusted. The Greek text that Hodges and Farstad published, “The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text,” (MGT) has many places where it follows the critical text and omits and changes words (Greek words). The Preface of the NKJV indicates that “The Majority Text [Hodges and Farstad, MG T] is similar to the Textus Receptus, but it corrects those readings which have little or no support in the Greek manuscript tradition” (Page xviii). Thus it is not a true TR text. Another point to be made is the Hebrew text used for the NKJV. The Preface says, “For the New King James Version the text used was the 1967/1977 Stutgart edition of the Biblia Hebraica, with frequent comparisons being made with the Bomberg edition of 1524-25.” (Page xviii, these page notations are from the New Scofield Study Bible, with the NKJV text and published by Thomas Nelson.) What that means is the NKJV Old Testament is base primarily on the ben Asher text which is the Critical Text of the Old Testament. That is why in many places the NKJV reads a lot like the NIV, NASB, ESV, et al. If you want to pursue this discussion and want evidence where the NKJV follows the critical text I will be happy to comply recognizing that my time is sometimes limited. My major concern is that some could be misled about the KJV and the arguments you (or maybe Joshua Teis) presents about the “dead words” and “false friends” is somewhat misleading. I have not posted any arguments against the things presented in this thread since there seems to be a dislike for any counter arguments of the article. [It is not possible to use italics here thus an omission of italics is to be noted where it is applicable.]

Jerry, I appreciate the further explanation—but let me say gently that you appear to be guessing at what my book must say! But I doubt that you could guess this accurately, because it’s an argument no one has made at any length before. I am trying to make a new contribution to the discussion, one that will bring peace, not a sword, as much as possible.

And the way I do that is by going completely neutral on textual criticism. If you think the text underlying the NASB is corrupt, I will not argue with you: I will just urge you to make or use a translation of whatever Hebrew and Greek texts you prefer into contemporary vernacular English that the plow boy can understand.

Brother, if you think the NKJV is dangerous because it includes alternate readings in the margin, I must stop to note that the KJV translators did the very same thing… before I go on to say again: then please, because of 1 Cor 14 and Matt 28, make or use a translation of whatever Hebrew and Greek texts you prefer into contemporary vernacular English for the plow boy—and leave out marginal notes about manuscript variants. (And if you can supply me with a list of passages in which the NKJV uses the critical text rather than the TR, I would very much love to see it! I have been diligently seeking such a list and have not been convinced by the one list presented to me. Oh—and James Price of the NKJV specifically claims that he personally made certain that the Hebrew text underlying the NKJV was identical to that underlying the KJV; you can read this in his response to D.A. Waite.)

If my arguments about dead words and false friends in * Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible* are misleading, brother, I am truly open to correction. Please feel utterly free to post them here. I simply want people to have the Bible in their own English, and over the years I have come to realize that in numerous places where I assumed I understood the KJV, I was in fact mistaken. Not because the KJV translators made errors; not because I’m a dummy (at least I hope I’m not!); but because language changes over time.

Greetings Mark. Thank you for opening the opportunity for further discussion on this subject. I have purchased the Kindle edition of your book and started reading it. I am not currently ready to respond with any evaluation. I would like to respond to two things you have stated about the KJV. You mentioned that the Jerome Vulgate (I assume that is the Vulgate you referenced) being the standard version for a much longer period than the KJV. There is one problem with that. The Roman Catholic Church (RCC) authorized (and probably paid for) the translation. It stood so long as the only version “authorized” because the RCC saw that no one would have a Bible in their birth language by threatening anathema on anyone who attempted to do so. The Vulgate was kept from the common people and only the Priests of the RCC were allowed to read it. I remember when the RCC had all their Mass Services in Latin which is another story. The tide against the Vulgate did not move until John Wycliffe translated the Bible into English. Thus there is a major difference between the RCC mandating the use of the Vulgate and the KJV being accepted by the believers of the churches for 300 plus years.

The other matter I want to address is the footnotes in the NKJV I mentioned. You stated that the KJV (1611 I assume) had notes in the margin, which is true. The difference is that the margin notes were suggested alternative words or translations that the translators considered. That is not the nature of the footnotes in the NKJV. They are statements that the selected text is not in the “best” manuscripts (MSS). That is a major difference. I plan to post some thoughts on the difference between the NKJV and the Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text (MGT). Interestingly, Zane Hodges and Arthur Farstad were the executive editors of the MGT. Arthur Farstad was the Executive Editor of the NKJV, with Dr. James Price, editor of the OT and Farstad editor of the NT. I can find no evidence that Zane Hodges was active in the NKJV translation. There is a major disconnect between the NKJV and the MGT that will be addressed later. I trust you will have a Merry Christmas and the blessings of the Lord be in your life.

Greetings Mark. Your statement about my comments about the NKJV are “simply and clearly false” needs an answer. I have been busy and not had a lot of time but want to address your statement. The Preface of the NKJV states, “The Majority Text is similar to the Textus Receptus, but it corrects those readings which have little or no support in the Greek manuscript tradition.” (page xviii, The New Scofield Study Bible, New King James Version published by Thomas Nelson). Here is an example that verifies that the NKJV does not follow the TR as some (even the publishers) want others to believe. An examination of Matthew 27:35 will demonstrate that the Majority Text (MGT) eliminates the same portion of the verse that the Critical Text does which is, “They divided My garments among them, And for My clothing they cast lots.” The edition of the NKJV I have has a note on this section: “NU-Text and M-Text omit the rest of this verse.” The version of the NKJV I have has this phrase in italics and is offset in the NKJV I have. This alerts the reader that it does not belong in the text to coincide with the note. I have collated several places in the MGT and it agrees with the Critical Text more times than some would like to admit. What does that do to the prophecy in Psalm 22:18? I guess it is an idle prophecy with no fulfillment. One other example is found in 1 John 5:7-8. Zane Hodges admits that this should not be in the text due to insufficient textual support. He states in an article in the Journal of Evangelical Theology, June 1978, after explaining the process of the development of the Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text says, “For example, the famous Comma Johanneum, the introduction of which into the TR by Erasmus is a standard piece of lore in text-critical handbooks, will be eliminated from our text. So will Acts 8:37 and many other readings that lack adequate MS attestation” (page 143). [Comma Johanneum should be in italics.] If you check the MGT you will find it is not there. This clearly indicates that the MGT of Hodges/Farstad follows the critical text in these places. It is definitely an eclectic text. So maybe my statement about the NKJV and the MGT are true after all.

Thanks for making us think this through, if (since) it is a question of origins and technics it shouldn’t matter what form the English is in.

For those who still want the thou, ye and ‘eth’ language KJ21 is for you; as it modernised the syntax only.

For a complete new / modern feel MEV is the one. I’ve not had a chance to try the kJVER yet.

Mr. Howard. May I suggest you look at Exodus 16:28. The NKJV says, “And the LORD said to Moses, “How long do you refuse to keep My commandments and My laws?” At first glance, you might think that God is suggesting that Moses has been refusing to keep God’s commandments and laws. Yet when you read the KJV it says, “And the LORD said unto Moses, How long refuse ye to keep my commandments and my laws?” (Exodus 16:28). The modern English does not have a way to distinguish between singular and plural in the 2nd person “you” without context. The KJV has a way of avoiding that problem when God said to Moses, “How long refuse ye to keep my commandments and laws?” The word “ye” in the KJV is always plural. Thus you know that God is talking about the people of Israel, not Moses. If it was talking about Moses the KJV would say “How long art thou [thou is always singular] refusing to keep my commandments and laws.” Maybe the KJV has some value that needs to be given attention. The KJV translators used the Old English which had been out of use in 1611. They knew that it enabled them to convey the exact meaning and nuances of the Hebrew (and Greek). Just a thought.

Josh, I must lovingly and compassionately call attention to the fact that you neglect to acknowledge a very key principle (though you do briefly acknowledge it in #1 of the 10, and if given more attention would show it contradicts your thrust here). The whole premise of your article that it ought be modern English, contemporary, understood by the plow boy (an archaic phrase on its own—have you seen a plow boy?—maybe in India, but I’d say not in the US) is weak because you skip over that the Bible says many times that God hides the truth at times from people to, as I would assess it, try to see the earnestness of their search after the truth.

Please read Isa. 6:9-10 which shows that God wasn’t burdened about making His word readily available widely to be understood immediately everywhere. Also, Jesus told parables in much of His public ministry for the expressed purpose of keeping the real meaning and truth away from people who had no heart to listen to it (Mt. 13:10-17 where He references Isa. 6). Many of the Bible writers, as the prophets, did not even understand everything they were writing, as Daniel in Dan. 12:8-9, or as others as told in 1 Pet. 1:10-11. The meaning was hid from them for a time, if not the rest of their lives. Even Peter, a contemporary of Paul, said of Paul’s writings that there were some things that were hard to understand (2 Pet. 3:15-16), demonstrating that God was inspiring into scripture through Paul what was even not completely understandable to the common person at the time of writing. So, to try to put it in understandable language everywhere is to seek for something God never absolutely intended.

Many appeals you make in support of your argument are unsuitable, and need clarification and/or retraction. You allude to 1 Cor. 14:9, but neglect to say that it is in context to what was being done in a church service, not how a Bible should read. It is a mistaken allusion. There are other statements by Paul that show the opposite, as in 1 Cor. 2:9-14 (please see the passage, not enough room here for it). Where are those deeper things of God as to be revealed to those that are spiritually discerning but in the word of God? In the same book that you allege Paul is advocating your idea, he is actually saying the opposite, that the word of God is what it is, in its simplicity or obscurity, and that we need to be led of the Holy Spirit to be able to truly understand it and discern it, that it won’t come naturally to all without His leading (see also John 16:13).

You advocate that it should be readily understandable by regular folks, but the need of pastors and teachers is stunningly overlooked or even abrogated by that. Remember, those are a gift of God to, and function of, the local church (Eph. 4:11-16). The reference to Neh. 8:8 by no means backs up your claim that God’s word should be in people’s common speech, but instead buttresses this point of the need of pastors and teachers. “So they read in the book in the law of God distinctly, and gave the sense, and caused them to understand the reading.” Ezra had just read for probably about six hours (v. 3) the Pentateuch in the original way it was written, Hebrew that was centuries older than what they spoke then, and so the need was for teachers to explain it to them. There was no call for or work by Ezra to put it in the then modern Hebrew instead. He just read it, and then it was explained to people. That is the model for all churches of all times. It was accessible to a point to them then, but it still needed to be explained by competent and knowledgeable Bible teachers.

A further example of that, in New Testament context, is how that in Acts 8, on the way back to Ethiopia, the eunuch replies to Philip that asks if he can understand what he’s reading in Isaiah 53, “How can I, except some man should guide me?” God didn’t have them concentrate on bringing the scriptures up to modern, common language, but had people explain what it said, competent, studious people. It is the need of personal workers, and then pastors and teachers in the church. That demonstrates Rom. 10:14.

In referring to Acts 2 you inadvertently diminish and distract from what it really was about. It was not God getting His word in the common tongues of all those people from various language groups to be understood and thereafter accessible to them, but those were mass witnessing encounters (as Philip in Acts 8); they were proclaiming the Gospel. The real point there is that God was using the miracle to try to establish the legitimacy of the Gospel, of what the Lord Jesus Christ had just done recently before then, and to confirm it to stubborn Jews (1 Cor. 1:22) that it was of God and they should accept salvation as obtained by their true Messiah. The miracle was incidental to the need to set the local New Testament church off and running, as a way of getting instant public credibility.

What you are doing (unwittingly I presume) is making a stand that the unbelieving Eugene Nida made, who championed an unfaithful translating style, more just a revival of the analogy type of interpretation as first introduced by Origen. He crafted the dynamic equivalency method, so that he could buttress his false principle, “the Scriptures must be intelligible to non-Christians.” What you are advocating is not far from that and yet eerily similar.

A good explanation was given by Robert Boyle the scientist (and a strong Christian) in 1661, 50 years after the KJB was finished. He said of the Bible’s writing style, “And as the knowledge of those texts that are obscure is not necessary, so those others whose sense is necessary to be understood are easy enough to be so; and those are as much more numerous than the others, as more clear. Yes, there are shining passages enough in Scripture to light us the way to heaven, though some unobvious stars of that bright sphere cannot be discerned without the help of a telescope.” (On the Style of the Holy Scriptures). There you have it, intentional simplicity and yet obscurity too. Simplicity for what is critically important to be simple (the Gospel), and yet ambiguity/obscurity for what is not all that urgent to know. Ward Allen said similarly (either him or the KJB translators), “Let it be granted that the Holy Ghost utters ambiguities, and ambiguity becomes in Holy Scripture a crucial matter, sometimes indeed a matter of life and death.” (Translating for King James, p. 13). Let the ambiguities be ambiguities if God saw fit to have them so. We are not in place of the Holy Spirit to solve all of them. By going and making clear in Bible translation what the Lord has not made clear in His word it breaks 2 Pet. 1:20, “Knowing this first, that no prophecy of the scripture is of any private interpretation.” That is a serious error. Maybe God has not allowed any modern version dominance and keeps on using and blessing the old KJB because they have by and large ignored his warnings and commands such as 2 Pet. 1:20.

Daniel, you’ve got a good head on your shoulders. You write clearly, and you know how to make an argument.

So please, brother, listen to your own argument. Are you truly against what Josh and I are arguing for (I worked with him on this post)? We want the freedom to use English Bibles that have been translated into the current English vernacular. That means probably three major things:

1. “Dead words” (archaic and obsolete lexemes) are replaced with living ones. “Besom” becomes “broom”; “chambering” becomes “immorality”; “emerod” becomes “tumor.”

2. “False friends”—words we still use but that meant something different in 1611—are replaced with contemporary equivalents of what the KJV translators meant. “Halt” in 1 Kings 18:19 becomes “limp”; “remove” in Proverbs 22:28 becomes “move”; “commendeth” in Romans 5:8 becomes “demonstrates” (or, and you’ll have to read my book to see why, even “showcases”).

3. Attendant features of language such as punctuation and paragraphing are done according to contemporary conventions. Quotation marks, colons, commas—all should operate in the way people today expect them to according to well established standards.

Brother, I’m trying to listen and understand. Is this what you’re saying?

– Because God judged the Israelites of Isaiah’s time and the Jews of Jesus’ time by hiding truth from them, and because God saw fit to make the full gospel a mystery until after Jesus’ resurrection, we should use dead words like “besom,” “chambering,” and “emerod” in our Bible translations? We should purposefully use words no one uses anymore?

– Because Paul wrote some things that are hard to understand, We should use false friends like “halt,” “remove,” and “commendeth”? We should purposefully use words in a *way* no one uses them anymore?

– Because the natural man doesn’t receive the things of the Spirit of God (1 Cor 2:9–14, the passage you mentioned), we should purposefully use punctuation and paragraphing conventions in our Bibles that are no longer used in contemporary English?

– Because Christ gives pastors and teachers to his church (and the Ethiopian eunuch needed Paul’s help to understand Isaiah), we should never need to update or revise our Bible translations?

I’m honestly not trying to put words in your mouth. I’m trying to understand your argument. I read you very carefully: this appears to me to be what you’re saying.

Would you apply this reasoning to new translations on the mission field? Translators should purposefully reach for obscure or archaic terminology when contemporary equivalents that are understandable to the man on the street are readily available?

Brother, I don’t disagree with most of what you say about Acts 2. Surely, yes, the major purpose of that event was to lend credibility to the gospel message and not to provide principles for Bible translation. But look at what the article actually says: Acts 2 “hints at the importance of using people’s common speech.”

And yet I’m afraid I find myself unpersuaded by your denial of the 1 Cor 14 argument above. All I’ve ever gotten from critics of my 1 Cor 14 argument is, in fact, simple denial: “It isn’t talking about Bible translation.” I still haven’t gotten an actual counterargument. I absolutely still stand on 1 Cor 14 when I say we must use intelligible words in church, and use them in our Bible translations. Edification requires intelligibility. Paul states and restates this principle in 1 Cor 14. I marked up the nine times (by my count) that he states or assumes this principle in that chapter. I cannot with good conscience see how someone can deny it.

Perhaps you genuinely misunderstood what Josh and I are saying. Maybe you think we’re saying, “We should make the entire Bible easy enough to understand that any kid could pick it up and get it.” Let me assure you: we’re not saying that. Yes, Paul wrote some things that are difficult to understand. Those things should remain difficult at the conceptual level. They should not be made extra difficult, however, by the use of dead words and false friends. In Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, I use the analogy of my drive home from work through the Cascade mountains. The driving may be difficult—going around corners near cliffs—but the asphalt should be as smooth as possible. The concepts of the Bible are often difficult; but the English generally need not be. We still stand with the plow boy.

Mark, thank you for replying, though I did address it to Josh since he wrote and published the article. I figured it was a joint work, but there was nothing to indicate such in the header to it, hence it was to Josh. I really am not going to take a whole lot of time to answer your comment since I am busy, and, not being curt or anything, you are not high on my priority list. Also, I really would have liked a more thorough response from you about “Study” in 2 Tim. 2:15 which I answered your comment with further information as well as what I had said before was by and large unanswered. I also find Mr. Rockwell’s comments intriguing, but those are left unanswered as well. His proof there obliges you to stop claiming that the NKJV was translated from the same texts.

Like I said, I’m not going to give much time to replying here since the further questions you bring up are not so much in context with what I said but more of a distraction from them. I have not read your book, so the only introduction to your theories about the KJB I have are here. I don’t plan on buying it either because I’m not the one that is calling for (*yet another*) modern version, and I am completely satisfied with the KJB (as everyone should be). Hence, you bring out in passing things you no doubt have gone into more detail in your book, and so I’m not going to try to answer your questions since there is a lot of missing information.

One thing I think that needs to be brought out, as evidenced by this comment and the article is that I don’t believe you or Josh are actually trying to define the KJB English. He claimed that when he gave time to define words in the KJB while teaching through Ecclesiastes and other books that the definitions ended up being just how modern versions put it. Now, he didn’t say where he got his definitions, but if I was a betting man, I’d be pretty sure he got them from Hebrew/Greek lexicons from modern “scholarship”, not actual English dictionaries as Webster’s 1828 or the OED.

So, he didn’t say so specifically, but I know from how you are defining some of these things that that is what you are doing. Take your example of calling for commendeth to be put as demonstrates in Rom. 5:8. You didn’t get that from an English dictionary. I know, because I looked at that long ago. Both WEB 1828 and the OED (Samuel Johnson’s 1755 either) do not define commend as demonstrate. You are just repeating what the NASV, NIV and NKJV have. So, in essence, you are doing a shell game, claiming these words must be modernized, when in all reality instead you are calling them to be changed to what modern versions have from their Greek “scholarship”. It always ends up like that, trying to make it sound like the honorable task of helping people with understanding the word of God is what is being called for, when in all reality it is a word by word changing it into something like the modern CT versions.

Now, to briefly make a statement on anything else, because I don’t trust your BDAG background, and whatever Greek education you have, I cannot say you are even properly understanding what should be put in specific places in the Bible. Hey, you are wrong about “Study” in 2 Tim. 2:15. It is not a “false friend” as you allege. You just somehow can’t see it for what it truly is, that they intended it to be primarily or solely understood as the learning kind of study. If I can with two words as here poke holes in your theories, the rest is simply needless.

“Chambering” is not exactly the same as “immorality”–immorality is an awful choice because it is way too generic and can be molded to whatever someone wants it to carry, as Pelosi stupidly calling Trump’s wall immoral, but yet celebrating infanticide (abortion) as though it is a human right, and therefore not immoral. Emerods and tumors are not exacts synonyms. Emerods are tumors, yes, but in a specific place, while tumors can be in any location. You are diminishing the word of God by changing the meaning to broader, more generalized terms, advocating that Deut. 4:2, 12:32 be broken therefore. Besom is still used in some parts of the UK, so it is not dead. Some of what I perceive your beef is is that you are against what are likely in essence British words, as besom. That is natural since that is where it was translated. By the way, the KJB manner of English was not spoken at the time necessarily–they coined at least seven words or terms for their translation, and the Dedication to King James shows that the usage of thee, thou, thy was on the way out at the time since they referred to him as “You” (other examples could be given from places like Lancelot Andrewes’ writings). There are many other things to demonstrate this.

Contemporary conventions in punctuation, quotes, etc. are hardly a reason to change it all; plus they change too, sometimes regionally. One thing from it bugs me especially: quote marks. You are calling for them, but you forget such places as 1 Chr. 23:5 and Acts 17:3 where it is impossible to figure out where a quote begins or ends, and therefore where quote marks would be put if used–and so putting quote marks would break 2 Pet. 1:20 since it is interpretive guesswork.

As for the rest of it, it all points to the need and obligation of the Bible reader to STUDY (2 Tim. 2:15), and for the pastors and teachers to also study, and teach it right. And, the whole matter of translation and what I advocate for it would necessitate a long, book-long response which I’m not going to do here. By the way, it was Philip in Acts 8, not Paul (I know it was a mistake).

Daniel, I will again let my case rest. You make some good points, you truly do. You may think that I am hopelessly corrupted by my use of critical text Bibles, but I think you are a gifted person whose abilities ought to be put to use for the good of Christ’s body. I hope they are. I am content to let readers decide for themselves between our respective viewpoints.

If anyone has gotten this far into the rabbit warren of the comments section—and this offer includes you, Daniel—I have a number of free copies of my book available and am happy to send them to anyone who will contact me privately. My email address is attached to this comment, and the contact form on my website is also a good way to reach me: https://byfaithweunderstand.com/contact.